Pyramid Dead

The Artangel of History

Myself and many other former Heygate residents have moved to inferior accommodation, thinking that we would have the right to return to brand new homes when the new flats were built. Now this will never materialise – we have been deceived. The council has been unscrupulous since the outset of the regeneration in everything they have done. This whole scheme has been a shambolic act of deception on a grand scale.

– Dylan Parfitt, ex-Heygate Resident

We hope the Pyramid will be a valuable addition to the cultural landscape of Southwark for the time that it is there, and a work of art that will continue to be talked about long afterwards.

– Artangel Planning Permission Statement on proposed Mike Nelson Pyramid on Heygate Estate, October 2013

Image: Artistic intervention on Lend Lease’s development banner on site of famous ‘NOW HERE’ graffiti on Heygate

(Re)-possessed By Art

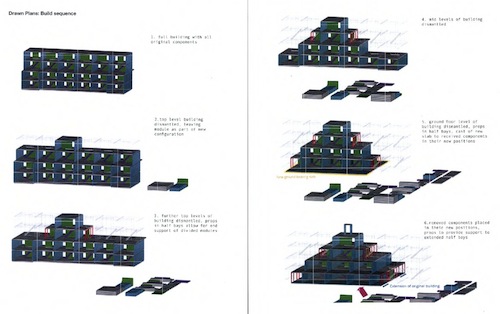

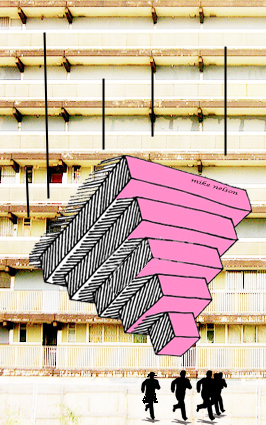

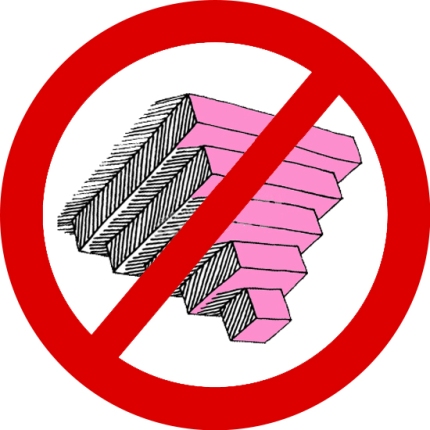

All over London, council estates are being emptied of their tenants on the grounds that large concentrations of working poor and unemployed people need to be moved out and replaced by mixed communities of owner-occupiers and private renters. Artangel, the prestigious London-based public art commissioners, working with artist Mike Nelson, spent over three years looking for a site for a big new work.1 When they found the emptied Heygate Estate in Elephant & Castle, South London, it perfectly fitted Nelson’s criteria for a 20th Century municipal building awaiting demolition. They decided to step heavily onto that site despite being advised not to by local housing campaigners, and sought to re-arrange one of the maisonette blocks into a ‘pyramid’-shaped public artwork.

But the site was becoming infamous. The removal of the Heygate residents was central to a wider and longer-term regeneration project at the Elephant. Without demolishing the estate and freeing up this land for private development not much could even start in this scheme. The struggle by residents against being shafted was a long protracted one stretching back to the late 1990s when the regeneration plan was just beginning to be drawn up. One of the important factors in these bitter struggles was to make sure that a counter-narrative could be maintained by residents against the spin and soundbites of the Council. Any press coverage secured by the Council was certain to contain its own double helix of justification for getting rid of the Heygate: the estate was a failure, full of crime and anti-social behaviour; its ‘revitalisation’ meant a much more positive arrival of thousands of new homes, hundreds of new jobs and a new park.2

Image: Diagrams for Mike Nelson’s Artangel pyramid scheme

Like most art projects made about estates, Council-sponsored regeneration likes to zoom in on the aesthetics of Council housing. This is an easy but dubious mode that highlights how an estate looks and how it is imagined to feel (by non-residents) while avoiding any understanding of how it is actually lived in, produced and experienced (by residents). It was normal for the Council to insist that the estate was not only ugly but also structurally unsound – ‘The Heygate is not fit for human habitation’; ‘It is not safe to allow people to live there’ – as if one must follow from the other.3 However the flats were large, well designed and popular and the Council’s commissioned survey of the buildings in 1999 reported that the buildings were structurally sound but needing loving care after years of neglect. Disinvestment by Councils is the standard strategy for creating ripe conditions for pro-demolition arguments to be put to the larger public.

Image: Community gardening on the Heygate Estate, 2013

The point here is that aesthetic focus on ‘ugly’ estate architecture incubates an assumption about the kind of people who might live there. Ugly buildings contain ugly people.4 Council leader Peter John described the estate as ‘a byword for social failure, for crime and anti-social behaviour’.5 What gets lost is the simplest point: the residents had done nothing wrong. They were secure tenants renting a home or leaseholders with mortgage on a flat, not criminals. However, because they had long ago been politically judged to be ‘the wrong kind of residents’ it was much easier to justify their removal, which had more to do with a future private development than with re-housing anyone in a dignified and fitting manner.6

Bad Publics Be Gone

Part of this regeneration argument is that ‘unlocking’ the mega-value of land benefits the local area more than having an Estate and its communities remain. Servicing the economy justifies all possible slurs, indignities and exclusions. Questioning why residents needed to be removed or why promised homes weren’t built to house the decanted tenants also comes to be seen by the Council as anti-social if it delays the regeneration process.

Alongside owning the actual physical properties of the estate buildings and land, the Council treated tenants and leaseholders as a kind of property that it could discard, sell or trash when it wanted too. The Council’s use of Compulsory Purchase Orders against some leaseholders came with public scrutiny of those residents who refused to leave because they were seeking a reasonable offer for the homes. The brutal and unnecessary CPO process legitimated a compulsory disenfranchisement of residents, performed on behalf of the Council and developers by the State as a kind of final legal rite of exorcism. Such storytelling about public housing and its residents was always part of New Labour’s concepts of social exclusion, anti-social behaviour and strategies of Neighbourhood Renewal.7 Reliance on stories of crime and decay ‘legitimated the displacement of public housing residents by systematically representing them as threats to the social body rather than as part of it’.8 With the emphasis placed on pseudo-scientific governance of ‘social exclusion’ and its reliance on its own half-truths of indexes and statistics, the agenda of ‘inclusion’ constructs a non-public who must be publicly disciplined. Personal attacks and blanket untruths attempt to de-legitimise public housing residents with a view to removing them entirely from the public, or rather from the wider understanding of who makes up a public. Being a public housing tenant marks you out as an irritant or pest. The expression ‘hygienic governmentality’ seems apt here.9 Some people’s opinions count but others’ must be disqualified on the basis of their mythologised status, i.e. because they’re council tenants. Regeneration seeks support for its social cleansing on the grounds that ‘abjected populations’ threaten the ‘good life’ that regeneration must promise: new private homes, new shops and new spaces; the thrill of an ‘urban lifestyle’. The implication that existing residents are the unlovable modern demons of the underclass – fatty single mothers of three, skinny junkies lurking on the landings, professional claimants living it up – enables the Council to displace its own brutality onto a supposed demand from a mythical general public to ‘sort it out’.

The Angelic Conversion: Artangel’s Housing Hits

When Artangel came to the Elephant with their plans for a new artistic wonder of the world, the site that was slowly coming to be known beyond the Elephant area as one where regeneration meant gentrification and social cleansing. What’s interesting is that Artangel’s desire to work on Heygate can be seen as part of their long track record of commissioning public artworks that use public housing and the ‘idea’ of home as their foundation.10 Their most famous hit is probably Rachel Whiteread’s casting in concrete of the inside space of a terraced house in Grove Rd, Bow, East London in 1993. Although the cast house may have looked impressive, there was very little to get your teeth into about London and its houses, their production and use in this very specific East End location. Any controversy and subsequent debates were more situated in local reactions from Tower Hamlets Council – who hated it and couldn’t wait to demolish it – than in anything ‘House’ was struggling to say.11 It was another step on the property ladder of casting for Whiteread, who has gone on to make negative space casts in repetitive and grander form ever since.

In 2007, Catherine Yass was commissioned to produce the work ‘High Wire’ at the soon to be demolished Red Road flats in Glasgow. Tightrope walker Didier Pasquette twice attempted to cross from the top of one tower to another but ultimately decided he would prefer not to. For Yass ‘the dream of reaching the sky is also a modernist dream of cities in the air, inspired by a utopian belief in progress’. This is an instrumentalisation of Red Road that does not attempt to explore what is actually in situ at the housing scheme. The art weakly balances itself on the symbol of a metaphoric tightrope walk. This is especially crap as the housing scheme remains incredibly contested along the lines of public housing histories, the myths of regeneration and latterly also the domestic politics of migration and resistance to the UK’s Border regime.12

One year later, in a further twist of ‘art saying nothing concrete’, Artangel enabled Roger Hiorns to make Seizure at a Southwark Council flat in Harper Road, near Elephant. Forty thousand folks travelled from all over London and beyond to visit the emptied council flat, now filled with growing blue copper sulphate crystals.13 Hiorns spoke of highlighting contradictions in public housing, where ‘in the great social experiment these buildings inferred[sic], they provided no room for movement, zero mobility to move further, they are completely static materially and emotionally’.14 Hiorns appears ignorant here and has probably never experienced the dynamic tensions, emotionally good and bad, of living on estates whereby day-to-day affinities grow, shatter and recombine perpetually as people come and go. Individual and collective pains or joys, problems or pleasures are shared both as product of the design but also how people choose to negotiate and use space materially. It can be an odd mix of the informal and porous cheek by jowl with the private and the aggressive but it is never ‘static’. Many reviewers would also describe the site with similar ignorance, e.g. as ‘well out of the way, in a part-abandoned social housing project in a part of town nobody goes to unless they happen to live there’.15 In a strange portent of the later Mike Nelson plan, these Harper Road flats were earmarked to be one of sixteen replacement sites for homes for those decanted from Heygate: homes that were never built.

Image: Counter-propaganda by Southwark Notes

Public Art, Private Wealth

So what is Artangel? Over thirty years it has managed to earn maximum credibility and props for commissioning and producing large-scale or ‘different’ on-site or site-specific pieces. Under James Lingwood and Michael Morris, Artangel takes State and private funding.16 It receives an annual Arts Council grant of roughly £750,000 but also relies on patrons contributing an unknown amount.17 ‘Company of Angels’ benefactors give a yearly donation of £600-£900, allowing access to Artangel-commissioned artists, openings and parties and annual ‘exclusive’ limited edition artworks. Or, for £5000 a year, the ‘Special Angels’ get all of the above plus an invitation to the annual Artangel dinner. A more significant funding stream is the much more loaded patronage of Artangel’s wealthy ‘International Circle of Friends’. There is also Artangel America for ‘private and charitable’ US patrons, operating with 501(c) 3 status so that gifts are ‘tax-efficient’.18 And Artangel has a board of Trustees including artists and curators as well as property developers, fund managers and private equity company founders the latter happy to reproduce the fine art of dispossession and displacement globally. Since many art institutions’ neoliberal turn, it no longer seems questionable to mix artists and high-end business people around the trustee table. This relationship between art and capital, once kept behind closed museum doors or in private artworld parties, is now happy to expose itself.19 Looking over some of the Circle on the internet there was a repeated motif of new money meeting mid-price modern art at auction and being very public about it. The urge to display the results of this collecting results in a refurbished multi-million pound house-cum-gallery and articles about it in newspaper supplements. A MYseum that exhibits the most tasteful parts of yourself to your peers. Your property and your art remain sound real asset investments with steady good returns. You will probably not be subject to regeneration and displacement.20 Elsewhere the crisis of housing and wages has a positive effect on those investments, as Ben Davis has noted sharply: the more low incomes are forced down, the more the rich art market expands.21 Full circle back to Heygate!

What better materialisation of the relationship between art and the current economy (and different classes’ relationship to property) than Artangel wanting access to Heygate’s concrete slabs – which were people’s homes – for use as components for an artwork? That this might come to be legitimised and permitted says more about property relations and value, however, than it does about the content of art per se. The fact that in shared decision-making with the Council Artangel had the prestige and privilege that local people definitely lacked was hugely symbolic of where real power lies and with whom and for what.

The Pyramid Scheme

The Heygate, now privatised, secured and to become only nominally public again, in part as a ‘semi-private park’, in the future Lend Lease development, was not given up lightly. Many local campaigns are still active at Elephant: Better Elephant, Elephant Amenity Network, People’s Republic of Southwark, Southwark Notes and 35% Campaign. All have been tireless in writing, publishing, holding meetings, film nights and anti-regeneration walks and, significantly, forcing the Council to account for itself through the Information Commissioner’s Office. These activities attempt to increase awareness not just of Heygate but also of what is happening in the wider Elephant & Castle ‘Opportunity Area’. Southwark Notes, for example, has been engaged in a research drive on the realities of Heygate displacement. Working with Heygate Was Home, a phenomenal web archive of bitter and sad testimonies from people who used to live on the estate, the displacement research was able to log and demonstrate through maps the real extent of the displacement.22

Image: Heygate anti-regeneration walk led by Southwark Notes, 2013

What was also unique on the Heygate during the decant was the takeover of the public land for continued communal use. Set in motion by some ex-Heygate residents and local people, there was an up and down flow of gardening, growing, allotments, polytunnels, parkour, graffiti and other imaginative outbursts, keeping chickens, pond-making, anti-gentrification walks, talks, meetings, poetry readings, sunbathing, dog walking, film-making, exploring, parties and so on.23 This was a small-scale and funny guerrilla war against the Council who were not best pleased with this common use. The occupation was also a very self-conscious practical strategy of defence of the estate’s history, maintaining its context as public housing but also keeping open the public and communal spaces.24 Without all this, less public discussion and knowledge of Heygate as a continuing example of what gentrification actually looks and feels like would have happened.

The news of Artangel’s designs upon the Heygate was only discovered by local groups as they were working with leaseholders on the estate. Artangel had contacted the last remaining leaseholders, more or less to tell them what they were hoping to do. There was no attempt by Artangel to seek genuine advice or comment on the plan from residents or local campaigns. In October 2013, some of the Southwark Notes group did force a meeting with the commissioner at Artangel responsible for the Nelson project after sending a long letter breaking down their opposition into two connected arguments. Firstly:

The Heygate Estate site contains both a serious and well documented history of poor judgement and poor treatment of residents by the Council and a well documented history of the struggles by those residents to maintain their dignity in the right to be treated fairly and rehoused in a manner befitting them. Just because a site becomes empty does not mean that it exists in a neutral vacuum. It contains a local memory and a local desire. In the same way we would say that art cannot then be produced on this site in a vacuum. If art is to be able to represent or make commentary on the world it is produced in, it has to be produced in some kind of context and that context is both in the realm of its production and its later reception.

Secondly:

A new and popular art work made from the material structure of the estate put on show for a publicly invited audience in a space where the space itself has been so hotly contested by residents for their homes and by those using the space for interim uses, would sound like it had been created with certain privileges that public art commissions can easily access but that local people could not. After the shoddy decant and resultant displacement of residents, the constant argument of the Council to clear the estate so that the much needed regeneration could happen, the recent fencing off of the estate denying access to numerous autonomous interim uses, we would view the then siting and invitation to an audience to view a new public artwork in this space as a gross act of symbolic violence that erases the long history and battles of local residents.

Image: Heygate Estate graffiti, 2013

Accompanying the letter were four short extracts from ex-Heygate residents’ testimonies outlining their anger and sense of betrayal about the decant programme.25 The meeting was held at Café Nova, upstairs at Elephant Shopping Centre. Two of Southwark Notes reiterated why it would be insensitive to those displaced to continue with the Pyramid project. It was a friendly if intense exchange. One proposal was to put Artangel directly in contact with the local campaigns, so that the curators could hear of the campaigners’ involvements on the Heygate and their feelings about the Pyramid. Southwark Notes also asked that Artangel send a reply to the initial critical letter.

Artangel finally replied that they:

“…don’t believe that Mike Nelson’s project, if and when it materialises on the Heygate Estate, will be inappropriate or disrespectful, and want to reassure you that what he has proposed to do is not intended to erase or aestheticise a particular political agenda, nor as a branding device for local regeneration [… ]. We’ve only recently begun to make connections locally, mainly due to continuing uncertainties as to whether we have the capacity and the resources to realise the project within the tight timeframe available. Now, having reached a point where we can make a formal submission for planning permission, it does seem like the right moment to broaden our connections”.

Southwark Notes now feel that the meeting and this ‘fob-off letter’ were only really about sounding out the opposition after Artangel had been confronted with a problem. They never followed up on the contacts offered. They simply couldn’t understand why the Pyramid was an insensitive project from the get-go. Mirroring the Council, Artangel sought no practical accountability to the site and its discontented residents and locals. Now that they had finally found a site for Nelson they were happy to go ahead with their desire to produce a ‘monumental and mute’ artwork on the Heygate. But in searching for a location (after they were previously set to go in another location that didn’t work out), they encountered the social housing context built into any work with the raw materials of people’s homes. Here the word ‘monumental’ is apt: the role of Artangel as enabler means an artist can come up with anything on the back of an envelope and Artangel cash and contacts can set it in process. But although such ‘art’ is in appearance an incredible feat (of building contractors!) it remains fairly superficial on a level of what it might mean or be about apart from being a monument to itself. There is certainly very little being said about the global increase in eviction and displacement as played out in one part of South London. It is doubtful that this even came into it for Nelson or Artangel.

Build Pyramid and They Will Come: A Day Out in the New Colonies

Local feeling was clear that this was a site that should not be opened up to an art audience for a day out. Any audience would only enter the site after it had first been made sterile, de-territorialised and re-territorialised as an artwork and place of cultural grazing. It would exist for a superficial and vile pleasure rather than an artistic engagement with the Heygate site and story and the wider housing economy story of London-wide regeneration, privatisations and displacements. ‘Art’ with such discontents displaced becomes only the material form and container of a modern consumer lifestyle. As with art, probably so with regeneration – ‘It’s all good!’ As such, art that’s as uncritical and bland as this mirrors how regeneration is also made to seem apolitical, a-historical and context-free. Regeneration place-makes non-places and in the same symbiosis ‘public art’ makes non-art.

London already has an ever-increasing number of these diverting spectacles either in temporary or permanent mode. The blog Homelesshome has described these public spectacles or faux-social spaces as ‘thingification’: ‘The law of the thing is that it must remain temporary. In this way it can easily be replaced by a new thing. And another. And another… Are you going to the ‘thing’ this weekend? Have you seen the ‘thing’? ‘Have you seen The Pyramid?’26 Measured more through numbers than critical commentary, success was guaranteed by the Artangel brand before the thing was even built or visited by anyone. Pure ‘experience’ and totally touristic, the artist acting as ‘the future engineer of entertainment, an activity that has no effect whatsoever on the equilibrium of social structures’, as Brazilian artist Lygia Clark put it in 1971.27 The empty site of Heygate and the Pyramid within offers up something more disturbing than just an emptiness or a void of meaning and intention. The site signals something more like a kind of modern impotence when faced with such degradations, a perfect symbiotic corollary for an audience on an artistic day out.28

Image: Men in suits, Heygate Estate, 2013

No Like Your Babylon Ziggurat

In the midst of the prospective monumentality, the actual ruination of the Pyramid came about as a bit of a surprise. Less spectacular than the Pyramid itself, its demise was more the result of a series of little chips and taps from articles, blog posts and open letters. On 12 December, The Guardian nationally rubbished the scheme in a very good piece, ‘Heygate pyramid: London estate’s evicted residents damn art plan’, placing ex-residents’ and local people’s views centre stage.29 Former Heygate resident John Colfer was precise in his criticisms:

We were the first people in, at the start of 1974 […] My father made the home a home, fitted new floors, everything. My parents never planned to leave the estate. So when you’re talking about using those same materials to make a pyramid, you just think: what is there to show that this was a well-loved home? These are our memories being turned into an artwork.

Later, poet Niall McDevitt’s ‘Open Letter To Artangel’ was also good.

No one doubts that the project will be artistic, but it is highly unlikely to be angelic. Artangel has not, in this case, given enough thought to the suffering of the victims of social cleansing or to the symbolism of the pyramid in such a context.30

He knew Heygate from poetry readings on the estate in 2011, reading his poem ‘The Human Elephant (In The Inhuman Room – For the Socially Cleansed)’ one evening amongst the trees. Artangel replied in private to Niall’s public ‘thoughtful letter’ with more fob: firstly, the ‘Pyramid’, as described in their own planning application, was actually a Ziggurat! Also, ‘within this context, Nelson’s project will activate a field of possible meanings rather than assert one in particular. If realised, it may be considered thoughtful, thoughtless, contentious, elegiac or any number of any things, but we struggle to understand how it would be seen as “aesthetic airbrushing”.’ They signed off with: ‘we welcome the measured nature of your letter and hope the discussion can continue in a similar tone’.

Between Artangel’s need to ascribe some importance to the Ziggurat and now non-Pyramid, their desire for nice and polite conversations about it and their own flagging up of the fact that they just didn’t get it, lies the reasoning at the heart of all opposition to the project. Art, its production and its reception, is again placed in a supposed neutral or non-implicated place whereby only the act of interpretation gives it legs (or takes them away). The production of art trumps any valid reasons for art or artists or Artangel actually staying away; art must be all good because by default it must say something about a situation. Ignorant of their own class power and the cultural capital that oils it, they still want to place art wherever they choose, even when told quite forcefully why it’s insensitive and dodgy by those who suffer the material consequences of demolition. It is of no value to these people that the Pyramid might be viewed as ‘contentious’. It is of less value and somewhat violent to say the Pyramid might be either ‘thoughtful’ or ‘thoughtless’. What was important was exactly that the Pyramid project was ‘thoughtless’ in relation to the history of the site and the people there.

Image: Map of Heygate Estate leaseholder displacees, 2013

Heygate Lives! The Pyramid Dead And Gone

On 20 December, the ‘Artangel Go Home – Pyramid A-Go-Go’ Twitter site was opened as another line of pointed inquiry into Artangel’s lack of understanding, and as the first indication of a public campaign working behind the scenes.31 On the same day, breaking their own and Council’s silence, Artangel let it be known that it was all over:

Over the past few months, we have had productive conversations with Southwark councillors, officers, and different interest groups in the borough. We are very disappointed by Southwark Council’s decision to stop Mike Nelson’s proposal progressing. We feel a great opportunity has been lost.32

It’s clear they had been dumped at the altar by Southwark and that they wished the Council had stuck to its initial enthusiastic support for the Pyramid. All that remained was a bizarre series of Tweets from then Artangel Chair Paul Bennun: ‘people like PyramidAGoGo royally screwed London & themselves’. Bennun, the boss of a new media company in Shoreditch, later continued in a frothy mode: the Mike Nelson piece ‘was one of the most important artworks of 21st C. And COMPATIBLE with residents’ understandable fury at gentrification’. Later he wrote that the opposition to the Pyramid was ‘conservative’ and ‘reactionary’ and that the Pyramid was a ‘GIFT’ to the campaigns and would have been ‘an incredibly beautiful testament to those forced to leave, keeping it in memory for all time’.33

Calling public art ‘compatible’ with the Heygate saga shows that there is no real understanding of the personal and collective stakes in this long struggle over public housing, public space, and still less of future struggles through which people might maintain themselves against such repression on top of austerity.

It was jarring that after cancellation Artangel tried to turn their insensitivity around by hinting that the work would have been a bonus for the local campaigns and that this was their, or Nelson’s, intention all along – the heavy political critique presumably going with the art territory. The Council’s support for it, though, was certainly not based on a pitch from Artangel telling them the artwork would send more negative PR vibes the Council’s way when thousands of art-goers had an epiphany about the social cleansing at work. The Pyramid project unintentionally says more about the actually existing un-niceties of regeneration, demolition, displacement, despair etc. Looking through the lens of how it was to be made says more about who has power than whatever it pretended to say to a discerning audience about estate living, housing policy then and now, poverty, domesticity, class and so on. Insisting that the age-old ‘autonomy of the artwork’ would do its magic work at a higher level cannot obscure the fact that only economic privilege can set in motion such an illusionary independence in the first place. Increasing your cultural capital and cultural value is often the bastard son of power and poetry.

What is interesting, though, is how little work it took to get the Council to go into damage limitation mode and pull the Pyramid. But it’s not like any other negative publicity around the decant, the consultation process, the wild activities on Heygate and the more disruptive protests at the two Planning Meetings in early 2013 had put them off doing anything they wanted before, so this is somewhat enigmatic.

On the Significance of a Refusal?

The last thing the Heygate needed was a public artwork and the claim that some random public reflections on the whole saga would serve anyone locally. The decant, demolition and privatisation of the Heygate Estate is a significant loss of necessary public housing and of political confidence among those with the least, who were attempting to keep hold of some small part of it. Although the dead Pyramid is a minor victory in the face of a much larger defeat, attempts to think about its significance can point to something radical and organised about this little refusal.

Image: Counter-propaganda by Southwark Notes

From the Council’s and developers’ point of view the loss of the pyramid is just an error or a blip in the overall programme. Artangel publicly tried and failed to produce another spectacular but were brought down by a Council fearing loss of control of their regeneration narrative. Behind that fear was the long work of local people, ex-residents, artists and writers and campaign groups in maintaining opposition to gentrification at the Elephant. In the miserable world of art and regeneration hybrids this was definitely one of the worst attempts yet, so it would be nice to think that this could be a kind of limit point, enabling more confidence in local counter power to the usual smooth ruining of things. It would also be useful for other sites of future displacement to see that refusal as a mode of resistance might take you further against gentrification than engaging in staged and faked consultations. This is certainly true at the Elephant, where next to nothing that benefits local people long-term has been wrested from the Council and its developers.

Turning up at a site of class cleansing, wanting to use what was now an empty space for art, Artangel created the perfect conditions for forgetting the prosaic, mostly poor lives of Heygate tenants, however they were lived. To describe those people as having a ‘cause’ only really highlights how alien their life is to some. Being thrown out of your homes is not a ‘cause’, it’s an effect of the ever-present global economy. Those people have also not gone away, they are merely living those same lives displaced to some other place. For the majority, being decanted to some other home has not improved or benefitted their lives. The Pyramid at best would have only abstracted any of these class relations or re-presented them aesthetically. It’s important to question and to map who is able to put this amnesiac magic into practice. The nub of this class question is simple: who has power, privilege and access to other money to make things happen and how do they try to avoid this misery being made genuinely public? Be it Artangel, the Council or developers, we find that the class question is the last thing they want to exhibit.

That’s why it’s important to maintain that ‘Heygate Lives’ here and now and in the future. This is not to obsess and be nostalgic or stuck but to keep that past very much activated to try to unstick what more may come. The fabric of the estate may go, the residents may be elsewhere, but the life of the place actually and symbolically remains and there are people locally holding onto that to maintain a politically live site against further monstrous regeneration.

THIS ARTICLE SOURCE: here

Footnotes

1 ‘Search For A Condemned Building’, Blueprint Magazine, 15 December 2009, http://www.designcurial.com/news/search-for-a-condemned-building

2 Numerous press articles of this sort can be found on the Heygate Was Home website. For example, ‘The Heygate Estate, which housed 700 people in what looks like a medieval blockhouse, and the Aylesbury Estate, with its 2,700 homes stretching south for more than a mile parallel to the Walworth Road, became sink estates plagued by crime, drugs and prostitution.’, http://heygate.github.io/press-archive.html

3 ‘Elephant & Castle housing delay “not acceptable” admits regeneration boss’, 11 November 2008, http://www.london-se1.co.uk/news/view/3600 and NBA Consortium Services Report May 1999, http://betterelephant.org/blog/2012/12/23/1998-southwark-housing-stock-survey/

4 Daily Telegraph journalist Simon Heffer has written, ‘Heygate was only built in 1968-69 and quickly became a sort of human dustbin. It exemplified the notion that if you give people sties to live in, they will live like pigs.’ Daily Telegraph, 18 September 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/columnists/simonheffer/8010830/Brilliant-architecture-can-rescue-even-Basingstoke.html

5 http://heygate.github.io/about.html

6 James DeFilippis and Peter North, ‘The Emancipatory Community? place, politics and collective action in cities’, in The Emancipatory City? Paradoxes and Possibilities, Ed., Loretta Lees, London: SAGE publications, 2004, pp.79.

7 See Ultra-red: Three Diagrams – Regeneration timeline: questions that may be useful to the people of Church Street posed from the experience of The Elephant and Castle regeneration programme, 2013.

8 Jamie Owen Daniel, ‘Rituals of Disqualification: Competing Publics and Public Housing in Contemporary Chicago’ In Masses, Classes, and the Public Sphere, Mike Hill and Warren Montag (Eds.), London: Verso, 2000, pp.62-82.

9 Lauren Gail Berlant, ‘The Face of America and The State of Emergency’ in The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship, Durham: Duke UP, 1997.

10 The Artangel website has an extensive section on all their projects including Whiteread, Yass and Hiorns: http://www.artangel.org.uk/projects

11 See, for example, former Grove Road tenant Stewart Home’s critique, ‘Doctorin’ Our Culture: On the KLF and Rachel Whiteread’, http://www.stewarthomesociety.org/klf.htm

12 On the spectacular hubris of Glasgow City Council regarding its Red Road tenants see, Leon Trotsky, ‘What the Fuck Are They Thinking…’, http://www.metamute.org/community/your-posts/what-…

13 Quoted from the long Southwark Notes webpage, ‘The Fine Art of Regeneration In Southwark’, https://southwarknotes.wordpress.com/art-and-regeneration/

14 ‘The impregnation of an object: Roger Hiorns in conversation with James Lingwood’,

July 2008, http://www.artangel.org.uk//projects/2008/seizure/a_conversation_with_roger_hiorns/q_a

15Hugh Pearman, ‘My blue heaven’, The Sunday Times, London, 9 November 2008.

16 Both arrived as long term friends at Artangel from Oundle public school via Oxford and then via the Institute for Contemporary Arts London.

17 Arts Council funding for Artangel: 2012-2013: £754,000; 2013-2014: £752,000; 2014-2015: £778,000,

http://www.artscouncil.org.uk/funding/browse-regul…

18 Despite this public funding and private patronage, Artangel still takes people on ‘unpaid part-time work experience placements lasting up to three months’, http://www.artangel.org.uk/about_us/opportunities

19 http://www.artangel.org.uk/support_us/artangel_international_circle

20 See ‘Art House’, The Observer, 13 August 2006, http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2006/aug/13/homes – ‘“I always think about where I’ll hang something when I buy it – if I don’t have space, I won’t buy.” As she walks from room to room, the art is the first thing she points out: “That’s a Douglas Gordon… This piece is a pumpkin given to me by Yayoi Kusama as a present when I left Japan… This is such a Tracey [Emin] work – you must read this, it’s so touching…”. The top floor of the house has been converted into a gallery. Greer lets non-profit organisations such as Artangel exhibit here, and shows her own collection for visitors’. Or ‘Net Wirth’, W Magazine, December 2009, http://www.wmagazine.com/culture/art-and-design/2009/12/iwan_wirth/ ‘They have an apartment on the building’s upper floors, where, every night during their New York sojourns, they offer the ultimate tribute to art by actually sleeping in a sculpture. Their bed is a typically ribald work by Rhoades, who gave it to them before he died, three years ago; it’s a plywood platform on overturned buckets, with lamps symbolizing female genitalia and Nineties porn magazines stashed in a cabinet.’

21 ‘…growing inequality was the key driver of the art market: “A one percentage point increase in the share of total income earned by the top 0.1 percent triggers an increase in art prices of about 14 percent”. It is indeed the money of the wealthy that drives art prices. This implies that we can expect art booms whenever income inequality rises quickly’. Ben Davis, ‘Art and Inequality’, in 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2013, p.79.

22 Campaign websites: Better Elephant betterelephant.org, Elephant Amenity Network elephantamenity.wordpress.com, People’s Republic of Southwark peoplesrepublicofsouthwark.co.uk, Southwark Notes southwarknotes.wordpress.com, 35% Campaign 35percent.org, Heygate Was Home heygate.github.io

23 Many of these activities are documented in Hector Castells Matutano film Heygate Diggers, http://vimeo.com/56528536

24 Ex-residents stories and testimonies can be viewed, read and listened to on the Heygate Was Home site, heygate.github.io

25 Personal correspondence with Southwark Notes, March 2014. All of the Southwark Notes/Artangel correspondence is online, https://southwarknotes.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/artangel-swark-notes-emails.pdf

26 http://homelesshome.blogspot.co.uk/2011/09/we-are-…

27 Lygia Clark, ‘L’homme structure vivante d’une architecture biologique et celulaire,’ in Robho, n. 5-6, Paris, 1971.

28 An interesting point is made by Antonio Negri, ‘Impotence is the very fabric of discoursing, of communicating, of doing. Not emptiness but impotence. The great circulatory machine of the market produces the nothing of subjectivity. The market destroys creativity’, from Antonio Negri, ‘Letter to Carlo on the Postmodern’, in Antonio Negri, Art and Multitude, Cambridge: Polity, 2011.

29 http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/12/hey… Worth mentioning that even before this article, Artangel were somewhat stuck in a bind with the blog coverage as they didn’t really want to make anything public before they had secured planning permission: ‘As you know, there’s been a certain amount of exposure of the project we’ve been discussing in the media. Nevertheless, we’ve agreed we would wait until the outcome of the planning application and only if and when it is approved release more information’ – Freedom of Information request by Chris Morris of communications between Rob Bowman and Southwark Council. In another email Artangel write from that bind that ‘we are slightly on the back foot in dealing with the media.’ https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/artangel_heygate_artwork_southwa

30 Niall McDevitt, ‘Open Letter to Artangel’, http://internationaltimes.it/open-letter-to-artangel/

31 https://twitter.com/PyramidAGoGo

32 Now removed from the Artangel website section ‘Press’, http://www.artangel.org.uk/about_us/press/press_re…

33 https://twitter.com/benoonbenoon/status/4205685859…

UPDATE: October 2014

asdasdasd

—

And here something for our Spanish speaking readers:

La pirámide Heygate: Residentes desalojados condenan proyecto artístico

Texto publicado en el periódico The Guardian, escrito por Peter Walker aqui.

La propuesta del grupo Artangel para desmantelar una de las cuadras evacuadas y reconstruirla como escultura cuando finalice el desalojo, despierta la polémica.

Como símbolo de la gentrificación vertiginosa de la ciudad, éste difícilmente podría ser más literal: en algunas semanas, después de que el último residente abandonó una propiedad desalojada del programa de vivienda de interés social en el sur de Londres, un equipo de trabajadores artísticos desmantelará una de las cuadras y la reconstruirá como una escultura en forma de pirámide gigante.

Ése es el posible destino de una parte del complejo habitacional Heygate en el cruce Elephant y Castle, ya que el ayuntamiento de Sothwark está considerando la propuesta del artista británico Mike Nelson, la cual ha sido calificada por antiguos residentes como insensible.

El ayuntamiento junto con Artangel –el influyente grupo que comisionó a Mike Nelson–, argumentan que el trabajo significa dar a este espacio un uso productivo y de creación, ya que permanecerá inútil durante meses antes de ser demolido para la construcción de nueva vivienda. Pero algunos habitantes de la zona consideran que una pieza de arte público (ya no se diga que se trata de una pirámide), no puede ser entendida fuera de su entorno social; justo en donde el último residente fue desalojado por la policía el mes pasado. “Considero que es una decisión terrible por parte de Artangel venir aquí”, dijo Chris Morris, un vecino que relata en un blog los esfuerzos por regenerar este espacio y que también se reunió con Artangel en octubre para expresarles sus preocupaciones. “Ellos tienen esta sencilla idea de que el arte conlleva cierta neutralidad que nos permite sacar nuestras propias conclusiones. Para nosotros, hay mucho más en juego”.

El complejo Heygate es una gigante edificación de concreto terminada en 1974, bastante popular y con gran cantidad de residentes que sufrió un deterioro gradual debido a la negligencia y a una muy poco merecida reputación debido a supuestos problemas sociales. El predio que alojó en su momento 3,000 viviendas populares ahora está siendo demolido para construir un desarrollo, en que el 75% de las propiedades serán vendidas en más de 380,000 libras (unos 8 millones de pesos), por un departamento de una sola recámara.

La propuesta de Artangel plantea “una impresionante instalación escultórica” creada por Mike Nelson, quien estuviera nominado al premio Turner y que representó a la Gran Bretaña en la Bienal de Venecia 2011, y para ser construida en enero de 2014 y abierta al público hasta el mes de junio, cuando el nuevo desarrollo comience. Nelson deconstruiría gradualmente una vivienda de 4 pisos y reconfiguraría los páneles prefabricados para crear una forma monumental que asemeje una pirámide, la cual podría ser escalada por los visitantes.

No es la primera idea del tipo planteada por Artangel. En 2008 presentó la obra “Seizure”, en la que Roger Hiorns vació 75,000 litros de sulfato de cobre en un departamento vacío del sur de Londres (también por demolerse), convirtiéndolo en una cueva con muros de cristales azules.

Mientras que “Seizure” ganó grandes elogios y significó para Roger Hiorns una nominación al Turner, el nuevo proyecto ubica a Artangel en terrenos más peligrosos. La reconstrucción de Heygate y la ampliación del cruce entre las vialidades Elephant y Castle han probado ser extremadamente controversiales, en concreto después de darse a conocer la planificación de una nueva cuadra que no alberga vivienda social, ya que el desarrollador argumenta que se necesitaría construir una entrada independiente y elevadores para ese efecto.

Mientras el ayuntamiento dice que el dinero que reciba por estas acciones significará la construcción de miles de viviendas accesibles en el perímetro, sus críticos señalan la expulsión de viejos residentes en la zona.

Para John Colfer, existe una preocupación aún más personal: los recuerdos de su niñez formarán parte de la pirámide. El ingeniero de 49 años creció junto con sus cuatro hermanos en Chearsley House, la cuadra que Nelson planea desmantelar, y de la que sus padres se mudaron hace dos años. Su abuelo murió en ese espacio.

“Fuimos de los primeros en vivir ahí, a inicios de 1974. Mi padre hizo de esa casa un hogar, cambió los pisos, todo. Mis padres nunca planearon irse de ahí. Así que cuando hablas de usar esos mismos materiales para construir una pirámide, te quedas pensando: «qué hay que mostrar, cuando ésta se trató de un hogar al cual queríamos tanto», éstos son nuestros recuerdos ahora convertidos en arte”.

Artangel señala que se ha entrevistado con cierto número de vecinos, incluyendo los habitantes de Heygate, antes de presentar el proyecto sobre el que se decidirá la tercera semana de diciembre. James Lingwood, codirector de Artangel dijo: “Sabemos que la cuadra en cuestión será demolida y que el entero conjunto habitacional ha sido desalojado. Este proyecto marcará un momento entre el pasado y el futuro del lugar”.

Pero Morris declara que algunos grupos han intentado utilizar partes de la propiedad para plantar vegetales y para su uso en exhibiciones de arte, pero que han sido impedidos por el ayuntamiento. “Pareciera que Artangel cuenta con el privilegio de acceso directo al ayuntamiento y con los desarrolladores, mientras que los vecinos no lo tienen”. Dentro de este contexto, es de esperarse que la elección de construir una pirámide haya extrañado a más de uno.

Una carta al departamento de planificación del ayuntamiento dice: “Dada la cantidad de ingeniería social que se necesitará después de la reconstrucción del conjunto Heygate, es posible que la pirámide sea una clara representación artística y cultural de quién ganó y quién perdió en este proyecto”.

El Heygate y su pirámide

marzo 15th, 2014 | Published in Opinión

Por Virginia Lázaro

Artículo publicado en El Burro, número 1. Madrid, Marzo del 2014.

Cuando comencé a escribir este artículo traté de ponerme en contacto con todas las partes implicadas: Art Angel, la comunidad del Heygate y Mike Nelson, por supuesto. Solo dicha comunidad implicada en el Heygate, a través de Southwark notes, tuvo a bien responderme. Fueron unas escuetas preguntas las que pude realizar pero, en mi opinión, de gran valor. Las transcribo aquí, al final del artículo, ya que por cuestiones de tiempo no fue posible incluirlas en la versión en papel.

English version of the interview with Southwark notes below

El Heygate es, aunque por poco tiempo, un bloque de viviendas de protección oficial construido en 1974 en el barrio de Elephant and Castle de Londres. Situado al sur del Támesis, Elephant and Castle pertenece a la zona de Southwark, la cual, es bien conocida por contener a su vez la Tower of London y el Millennium Bridge, el Globe Theatre y la Tate Modern, The Shard y la torre Strata… Southwark es, además, parte de Inner London, área formada por los barrios que se consideran el corazón de Londres; el londres real dicen. Como todos los centros de las ciudades, éste proporciona puestos de trabajo, genera actividad económica e influye en el PIB. Es de por sí un área a mantener, preservar y hacer prosperar pero da la casualidad, además, de que Inner London es oficialmente la zona más rica de Europa. Desde hace muchos años Inner London se ha visto sometido a diferentes procesos de gentrificación y reforma a través de diferentes demoliciones a gran escala y de varias regeneraciones urbanas.

Se ha escrito mucho acerca de lo especial y espectacular que es el caso de Inner London, el cual, ha llegado a ser calificado como un caso de “super-gentrification”. Este término fue acuñado por Loretta Lees, quien lo definía como una variación del clásico proceso de gentrificación, ahora mucho más diverso, debido a los grandes tamaños de las ciudades. Los proceso de gentrificación provocaban transformaciones urbanas en sectores deteriorados o en los que se encuentra una población mayoritariamente de clase trabajadora. En ellos, los mecanismos de mercado, mediante la variación forzada del precio del solar urbano hacen que la comunidad del barrio sea desplazada y excluida hacia otras zonas de la ciudad, normalmente más alejadas del centro. La población era progresivamente sustituida por otra de un mayor nivel adquisitivo. En definitiva, un proceso de reconversión e higienización urbana, recalificación urbanística, revalorización del precio del suelo, variación en el régimen de propiedad, etc. La super-gentrificación es una vuelta de tuerca del asunto. En este caso el proceso ocurre en zonas que ya habían sido sometidas previamente a procesos de gentrificación. Ahora la comunidad que se ve afectada es aquella que se había establecido allí como sustituta de la comunidad original. La mayor parte del Londres central (Inner London) ha pasado por varios procesos de transformación, pero todos sabemos que un barrio es la gente que lo ocupa, y por eso es muy importante decidir con cautela quién habita las casas del centro de nuestras ciudades. Londres lo sabe, Inner London lo sabe y el ayuntamiento de Southwark también es consciente de ello. Como dice su página web: “Nuestra fuerza es la gente”.

Hace unos años el área de Southwark entró en un proceso de regeneración, y reforma tras reforma, poco a poco, está convirtiéndose en un adorable vecindario. Desde Peckham, Nunhead, Camberwell a Walworth y Bermondsey, barrio tras barrio se están viendo sometidos a procesos radicales de reconversión. En los 90 llegaron la Tate Modern y el Globe Theatre a Bankside, después The Borough Market y el reciente rascacielos The Shard en la zona de The Borough… Interminables ejemplos que están transformando la parte sur de Inner London en otro agradable lugar donde ir de compras, comer, tomar café y donde quedar con tus amigos para ir de galerías y hacerse después con un tarro de mermelada artesanal. Tras un proceso como este se consigue, no solo generar capital económico, sino además importantes beneficios intangibles de igual o más valor. ¿Acaso no es ahora Bankside un barrio más agradable? Lleno de lugares de toda la vida donde comer una deliciosa comida local en tu paseo por el río desde el Museo del Diseño hasta la Tate Modern… Como ya hemos dicho, la recuperación de las zonas centrales de las ciudades, llamada eufemísticamente regeneración, se realiza en aras de la explotación inmobiliaria. Tras grandes procesos de desinversión, es el momento perfecto para una revalorización del área y una nueva demanda residencial. Los efectos de estas dinámicas inmobiliarias son dramáticos: exclusión de los residentes locales desplazados a la periferia de la ciudad y un consiguiente impacto en los modos de vida y costumbres. La historia del barrio y el valor inmaterial que previamente se había generado de manera espontánea desaparecen. Las costumbres locales han de dar paso a todos estos nuevos modos de vida que traen consigo los nuevos edificios, los nuevos inquilinos, los nuevos servicios de la zona…

Elephant and Castle se encuentra en pleno proceso de recuperación. Este barrio, de tradición obrera, ha sido desde el siglo XIX una zona un tanto olvidada. Quedó arrasado con los bombardeos de la II Guerra Mundial y tras ello, se llevó a cabo una reconstrucción poco exitosa. Ahora se presenta como una puerta de entrada hacia la parte sur de la ciudad, aún por explotar. Además, Elephant and Castle se encuentra en una situación geográfica muy cercana a La City y el West End, lo que la convierte en una zona especialmente interesante ya que allí las propiedades pueden alcanzar un altísimo valor inmobiliario. La transformación prevista incluye una nueva zona comercial, residencias de lujo, un mega-complejo de hoteles, cientos de nuevas casas y bloques privados… Se prevé una inversión de £3 mil millones de libras y unos 15 años para terminarla. Ya en el 2010 se inauguró la torre Strata, el rascacielos más alto de londres dedicado a viviendas de lujo, y hay que admitir que es un rascacielos realmente reseñable en el skyline sur de Londres (si es que acaso un skyline es reseñable). En aquel momento fue considerado un símbolo de esperanza para una zona tan deprimida, y no está exento de ironía el asunto, ya que la esperanza más bien debería tener la forma de una universidad popular en vez de un rascacielos. Se esperaba que trajera consigo un futuro mejor para Elephant and Castle, que nunca ha tenido muy buena fama, aquí, en Londres. Pero en realidad fue construido con intención, como los mismos dueños declaraban, de atraer a un sector con mayor capacidad económica que la de los residentes de la zona. Como ya sabemos, la fuerza del ayuntamiento de Southwark es la gente, y su esperanza reside en los nuevos inquilinos que la regeneración ha de traer consigo. La Strata es solo la punta de lanza del devenir gentrificado de Elephant and Castle.

Cuando la strata llegó a Elephant and Castle, el Heygate ya se encontraba allí y desde entonces han tenido que convivir juntos. El del Heygate ha sido un proceso dramático y polémico, y quizás la parte más visible del proceso de regeneración de Elephant and Castle. Diseñado por Tim Tinker, se construyó como un edificio perteneciente a la arquitectura brutalista. Se trata de una serie de inmensos bloques de cemento y hormigón, muy cercanos a idea de la Unité d’Habitation de Le Corbusier. Posee áreas comunales internas, tales como jardines, comunicadas por pasarelas con la intención de hacer más fáciles los accesos a sus habitantes. En total está compuesto por un total de 1100 viviendas en las que vivían unas 3000 personas. Elephant and Castle ha sido siempre una zona con una pesima reputacion, conocida por su alta tasa de criminalidad. Además, siempre ha tenido un gran número de bloques de viviendas estatales y esto suele traer consigo la preocupación de la gente. El Heygate no iba a ser menos y también se granjeó una pesada fama por padecer problemas sociales, violencia y altos índices de criminalidad. Con el paso del tiempo, a la vez que aparecía esta terrible reputación comenzó a darse un abandono gradual del edificio. La gran mayoría de los habitantes del Heygate han declarado que esta fama era en gran parte inmerecida manifestando, además, el sentido de comunidad que se fomentó allí desde el comienzo. Una comunidad que, sin duda, hemos podido ver unida desde los primeros conflictos surgidos con el ayuntamiento de Southwark. Sea cierta o no esta mala fama, ha sido muy polémico, largamente comentado, y una medida de presión muy grande de cara a la opinión pública.

Un día, de repente, se les negó a sus habitantes el derecho a decidir sobre el futuro de sus casas. El Heygate había de ser derribado y la única explicación que les dio el ayuntamiento de Southwark es que ya no tenía el dinero necesario para mantenerlo. Comenzó el drama, y poco a poco los habitantes fueron obligados a vaciar el edificio a pesar de que gran parte de sus inquilinos no querían hacerlo. Sus residentes comenzaron a abandonarlo en el 2008. El último habitante fue desahuciado por la fuerza en noviembre del 2013, después de años de lucha contra el ayuntamiento, intentando obtener un precio justo por su casa. Se habían prometido nuevas viviendas en la misma zona, pero muchos de los espacios que habían sido destinados a estas viviendas pasaron a ser espacios verdes y áreas de juego, o simplemente, no habían sido construidas en el momento en que los inquilinos tenían que abandonar el Heygate. Había previstas 1.100 nuevas viviendas, cifra que se vio reducida a apenas 419, de las cuales sólo 209 estaban terminadas para Enero de 2013. Han sido muchos los casos y muy diferentes las soluciones impuestas para hacer a la gente abandonar el Heygate. Se les ha obligado a aceptar casas que no querían, se les ha hecho chantaje, se les ha amenazado, cerca de 80 familias han visto cómo se habrían procesos de desahucio contra ellos… Todos los habitantes del Heygate, a quienes el ayuntamiento les había o concedido esos pisos con la idea de un futuro mejor, se han visto obligados a abandonarlos para dar paso a un mercado inmobiliario de lujo. En febrero del 2013, el ayuntamiento de Southwark vendió las 9 hectáreas de terreno en que esta emplazado el Heygate a Lend Lease Group por £50 millones de libras. En esa fecha, el consejo se había gastado ya £44 millones en vaciar el lugar y £21.5 millones en planificar el nuevo proyecto. Las contradicciones son innumerables, pero lo importante es que Lend Lease Group promete ahora dar un salto cualitativo: de un edificio fracasado a uno de los barrios más vibrantes y efervescentes de Londres.

Esto no termina aquí, aún hay un poco más. Bien es sabido que los procesos de gentrificación gustan de tener el arte bien cerca. El proyecto de regeneración del Heygate no iba a ser menos. El derribo ha de ser completado en este año 2014 y con él, dar paso a las 2.500 casas, los 178.000 metros cuadrados de tiendas, restaurantes, oficinas y espacios comunitarios, culturales y de ocio. Todo por cortesía de Lend Lease Group y el Southwark council. A pesar de que un derribo es un tiempo de trabajo, desgraciadamente no es un proceso de producción. ¿Cómo rellenar ese tiempo y ese espacio de vacío? Todas esas hectáreas esperando a ser explotadas de nuevo… Art Angel, una organización artística fundada en Londres en 1985 decidió, junto a Mike Nelson, nominado al premio Turner, realizar una propuesta al ayuntamiento de Southwark. Consistía en una instalación inmensa: deconstruir gradualmente un bloque de cuatro pisos y con los paneles obtenidos construir “una forma monumental semejante a una pirámide”. Además, dando acceso a la gente a visitarla y caminar por ella. El 20 de diciembre de 2013 el ayuntamiento comunicaba que el proyecto no salía adelante. Pero no es la primera vez que Art Angel propone algo similar. En el 2008, junto a la Jerwood Charitable Foundation organizaron Seizure dentro de un piso de otro bloque de viviendas de protección oficial ya vaciado en el barrio de Peckham. El artista, en este caso Roger Hiorns, cubrió por completo el interior de la vivienda con cristales de sulfato de cobre líquido. No debía de estar tan mal la pieza ya que Hiorns fue nominado al premio Turner un año después precisamente por Seizure. Además, el 15 de junio de 2013 el Arts Council Collection, dirigido por el Southbank Centre, la adquiría para exponerla al público en Yorkshire Sculpture Park con un periodo de 10 años de préstamo. Quizás tengamos que dar las gracias a Art Angel por hacer estos usos tan poéticos del dinero público y de los espacios abandonados, aquellos en los que parecía que no podría pasar nada más. Quizás Art Angel y sus artistas sólo estén realizando esfuerzos por salvarlos y traer, una vez más, experiencias dentro de ellos… Yo, por mi parte, nunca he padecido de una conciencia romántica y creo que el arte contemporáneo tampoco lo hace. Por otro lado, Nelson y Art Angel son muy claros cuando argumentan que lo que quieren es dar un uso productivo y creativo al espacio. Juntar creatividad y productividad ya me parece, de por sí, peligroso, pero hacerlo para ponerlo al servicio de aquel terreno público que ha sido vendido a una macro-empresa para una mejor especulación, es cualquier cosa menos romántica. Como ya hemos aprendido, las cosas que no producen no deben existir y aquellas que estan vacías, son el lugar idóneo para crear una infraestructura de explotación, en este caso, al servicio de Art Angel y Mike Nelson.

Alrededor del asunto pirámide se creó un gran revuelo. Un gran grupo de trabajo compuesto por ex-residentes, diferentes colectivos, académicos, artistas y gente de Elephant and Castle estaban organizando una campaña masiva en su contra, con intención de ponerla en marcha este año 2014. La comunidad del Heygate se quejaba de que este proyecto resultaba ofensivo y poco sensible para con aquellos que habían vivido en el Heygate. Sin duda, lo es, pero eso implica meterse en terrenos relativos a la ética y está claro que ésta es diferente para cada uno. Proponer una instalación artística en un lugar con una problemática tan compleja como la del Heygate no implica necesariamente estar concienciado con ella y querer responder a su situación tomando parte en el debate público. Pero no seamos cínicos, no hacerlo -no implicarse en la situación del lugar- ya es hacerlo de alguna manera. En este caso Mike no ha optado, por ejemplo, invertir tiempo y trabajo en la comunidad afectada, o por tomar una postura respecto del conflicto social o cualquier otra cosa que tomara en cuenta la historia de lo allí ocurrido. Mike parece solo preocupado de hacer un trabajo, simple y llanamente. Podríamos pensar, por un momento, que en su propuesta hay escondido, alguna traza de ironía. Queriendo convertir el inmenso Heygate en una tumba egipcia, en un proyecto faraónico, el cual, dará paso, como culmen, a un proyecto aún más faraónico como es el de la gentrificación de Elephant and Castle. Como metáfora muy cursi de lo que fue Elephant and Castle que da paso, tras de sí, a lo que ha de venir. En mi opinión, está fuera de contexto debatir acerca de la calidad de la propuesta artística, si lo hacemos olvidando los condicionantes de la misma. Es decir, esta pirámide ha sido propuesta de determinada manera y en determinadas circunstancias. Eso es así. Una obra es también su contexto, desde luego, y la misma obra cambiaría radicalmente si se hubiera hecho de otra manera, por ejemplo y sin ir más lejos, si se hubiera propuesto desde la comunidad del Heygate. No sé en qué momento se pensó el arte como algo autónomo de las cuestiones sociales, pero casos como este ponen más que en evidencia que no lo es. Quizás, sin querer, de manera no intencionada, pero la conclusión es que Mike Nelson quería ver pasear a las familias del Heygate, aquellas que han sido obligadas a abandonar sus casas con la subsiguiente pérdida económica y de derechos. Quería verles pasear por la pirámide y que los demás visitantes contemplaran junto a ellos las paredes de su salón, de su cocina y de su baño, allí, expuestas. Quería que se hicieran fotos el domingo por la tarde para subirlas a Instagram. Yo, ahora me pregunto, ¿estás intentando ser irónico, Mike Nelson? porque no entiendo como funciona esta ironía. ¿Estás intentando hacer olvidar al arte que existe para la gente, y no a su costa? Veo que ya no es necesario revestir estos proyectos de arte público y demás trilladas ideas de “Beneficios Comunitarios”. Ya no es ni siquiera necesario parecer un buen samaritano para los pobres de Elephant and Castle. En esto, estoy contigo, Mike Nelson, esto es lo que hay y no hay porque ocultarlo más. El arte funciona como cualquier Lend Lease Group, y esta pirámide no es más que una inversión para el futuro. Aun así, me hubiera gustado saber que opinas acerca de las reivindicaciones de los colectivos implicados en el Heygate con una postura crítica, o que te parecen los conflictos que se han desatado con todo este asunto pirámide, o que opinas de la relación entre arte y conflictos sociales…

Desgraciadamente, la historia de las ciudades es una historia creada por las grandes inmobiliarias, las entidades bancarias y las planificaciones políticas. Poco a poco se van borrando los rastros del pasar del tiempo, pero no porque la ciudad siga adelante, construyéndose una sobre la anterior. Si no porque las identidades están al servicio de los grandes emprendimientos especulativos. La historia del arte se escribe de la misma manera. Llegados a este punto, a mi solo me queda por decir: basta ya de usar el arte de esta manera. Basta ya de artistas irresponsables, y basta de dar crédito a gente que entiende así la vida. Por eso, deberíamos ser más cuidadosos al elegir las palabras con las que nombramos las cosas.

Entrevista realizada a Southwark notes. English version below

¿Que hay de cierto en los rumores acerca de la violencia y los conflictos sociales dentro del Heygate? ¿Se ha exagerado como forma de ejercer presión en la opinión pública?

El Consejo (ayuntamiento) ha usado esta historia del Heygate de un lugar que se había llenado de delincuencia y comportamientos antisociales pero las estadísticas de delincuencia de la Policía no respaldan esta historia del Heygate como un lugar peligroso. Todos los residentes que hemos entrevistado han hablado del sentido de comunidad en el estate y de cómo la gente cuidaban los unos de los otros. Esta era la razón por la que la gente no quería que la comunidad fuera dividida.

¿Ha habido alguna propuesta para una instalación artística? Una propuesta que se hiciera a la comunidad del Heygate en lugar de al consejo de Southwark

Desde el comienzo de la expulsión de los residentes mucha gente de Southwark Notes se involucraron en el funcionamiento de todo un programa de diferentes eventos alrededor de las zonas comunes. Ha habido numerosas actividades culturales dirigidas por gente local como proyecciones, charlas de artistas, lecturas, paseos anti-gentrificación, graffitti, cine , etc. Una pequeña comunidad de jardineros convirtieron las zonas verdes en áreas de cultivo de hortalizas y plantas y pasaron a ocuparse de estas áreas. Todas estas actividades eran constantemente amenazadas por el Consejo, ya sea por medios legales o simplemente con interferencias comunes.

¿Hay una comunidad artística conectada al Heygate? ¿Hay un registro de su trabajo on line que podamos consultar?

Como hemos dicho anteriormente, todo tipo de actividades interesantes estaban sucediendo. Estos son algunos enlaces :

http://thenewnature.wordpress.com/2013/05/19/heygate-urban-forest/

http://unemployedcinema.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/heygate-real-estate-horror-special.html

http://elephantandcastleurbanforest.com/maps/2011HeartofElephantandCastleUrbanForest.pdf

http://estellevincent.com/section330916_498359.html

El arte siempre está presente en este tipo de procesos, ¿cómo se está utilizando en el proceso de regeneración y posterior aburguesamiento de la zona de Elephant and Castle ?

Curiosamente para una actividad de proceso de regeneración, el arte y la actividad cultural que trabajan con la regeneración ha sido bastante pequeño en el área de Elephant (a diferencia de otros sitios con importantes procesos de regeneración a nivel local como Peckham). La pirámide de Mike Nelson fue la única cosa importante que se intentó colocar como arte público en una zona en regeneración, con todas las contradicciones y los descontentos que rodeaban a esa idea. Probablemente se debe a que se ha realizado como una obra de arte público que quiso ser impuesta a la comunidad. Art Angel no asume un verdadero diálogo con la gente local y con aquellos que han tenido un papel crítico y activo en el proceso de regeneración.

¿Ha tenido alguna conversación con Mike Nelson o Art Angel? Aparte de las cartas abiertas que hemos podido leer. ¿Han intentado Art Angel o Mike Nelson ponerse en contacto con la comunidad para informarle sobre la pirámide ?

Southwark Notes se reunió con Art Angel después de que escribiéramos una fuerte condena a la idea de utilizar las casas desalojadas como materia prima para una obra de arte público. Fue una interesante reunión en la que expresamos nuestra consternación por su ignorancia y falta de sensibilidad por el Heygate. Después de esta reunión recibimos una carta mal argumentada explicando que la pirámide no sería utilizada por el Consejo como relaciones públicas en su plan de regeneración y que la obra de arte puede ser interpretada de muchas maneras, algunas buenas y otras malas. Este argumento liberal sobre cómo el arte está abierto a hacer preguntas no era suficiente para satisfacer nuestra consternación ante el deseo de Artangel y el Consejo por ver el Heygate como algo con lo que se puede jugar para, además, un público no local en su mayoría. Hemos sostenido que la política del Heygate y el cruel desplazamiento de cientos de personas es más importante que el ser privilegiado culturalmente para conseguir lo que deseas, mientras que la población local no puede acceder ni a un proceso democrático, digno y responsable con respecto al proceso de regeneración de la zona.

Ofrecimos varias veces la posibilidad de poner personalmente a Art Angel en contacto con cuatro grupos locales que han estado activos desde hace años en la campaña para un proceso de regeneración más justo y con beneficios para todos (no sólo para los inversores y compradores de viviendas) pero no quisieron hacer frente a estos grupos.

No hemos tenido ninguna conversación con Mike Nelson ni sabemos lo que piensa de la cancelación de la obra de la Pirámide.

¿Conoceis la opinión de Mike Nelson sobre los conflictos sociales y políticos generados por la propuesta? ¿Creeis que si Mike hubiera estado en contacto con la comunidad, si hubiera propuesto el proyecto a la comunidad y hubiera estado trabajando con ellos desde el punto de vista del encuentro entre lo social y lo artístico, la gestión del dinero público, etc. la reacción a la pirámide hubiera sido diferente?

La forma en que la pirámide llegó a nuestra comunidad fue muy similar a la forma en que llegaron los encargados del proceso de regeneración. Ellos aparecen un día y te dicen lo que va a suceder. Si Art Angel hubiera intentado preguntar a la gente local lo que pensaban de esta pirámide que podía haber encontrado algunas simpatías y un proceso real con el que aprender y descubrir si era una buena idea. En vez de esto, optaron por creer que su estatus y prestigio significaba que a) la Pirámide era obviamente un “algo bueno”, y b ) que podían salirse con la suya porque eso es lo que ellos esperan.

Southwark Notes y la gente con la que trabajamos en contra de la Pirámide estamos contentos de que la pirámide no ha seguido adelante. Empezamos a oponernos a ella con la creencia de que no debía suceder y como un rechazo a esta actitud de carácter colonialista por el que las zonas de clase obrera son vistas como lugares listos para hacer lo que les venga en gana.Esta es la única manera en la que las comunidades pueden mantenerse firmes y exigir una toma de decisiones abierta y responsable.

English version of interview with some of Southwark Notes on the Pyramid for above article:

What is true in all the rumors about violence and social conflicts within the Heygate State? It was an exaggerated situation or as a way to exert pressure on public opinion?

The Council has been using the story that the Heygate Estate as a site of public housing had become a a place full of crime and anti-social behaviour. Police crime statistics do not back up this narrative of the Heygate as a dangerous place. Residents that we have interviewed have all spoken warmly of the sense of community on the estate and how people looked after one and other.It was for this reason that people did not want the community to be broken up.

Did you had any proposal for an artistic installation? A proposal made to the Heygate community instead of the Southwark council ?

Since the start of the removal of residents from the estate, many people included Southwark Notes people had been involved in running a whole programme of different events on the estate in it’s communal areas. There have been numerous cultural activities run by local people there such as film shows, artists talks, readings, anti-gentrification walks, graffitti, film making and so on. The garden areas were also turned into growing areas for vegetables and plants creating a small community of gardeners who would look after these areas. All of these activities were constantly being threatened by The Council either through legal means or just general interference.

Are there an artistic community, connected to the Heygate?. If any, there is a record of their work on line to share?

As we said above, all sorts of interesting activities were happening. Here are some links:

http://thenewnature.wordpress.com/2013/05/19/heygate-urban-forest/

http://unemployedcinema.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/heygate-real-estate-horror-special.html

http://elephantandcastleurbanforest.com/maps/2011HeartofElephantandCastleUrbanForest.pdf

http://estellevincent.com/section330916_498359.html

Art always like being around these type of processes, How is being used in the regeneration process and subsequent gentrification of the area of Elephant and Castle?

Interestingly for such a big regeneration process, art and cultural activity that works with regeneration and developments has been fairly small in The Elephant area (unlike other major sites of regeneration locally such as Peckham). The Mike Nelson pyramid was the only real big thing that attempted to place a public art in a regeneration zone with all the contradictions and discontents that surround such an idea. It is probably because that little cultural work within the regeneration process had happened that such a ‘top-down’ public artwork was attempted to be forced on the community. Artangel did not undertake any and serious real dialogue with local people and those who have been actively critical of the regeneration process.

Have you had any conversation with Mike Nelson or Art Angel? Apart from the open letters we could read. Has Art Angel or Mike Nelson tried to contact with you or your community to tell you about the pyramid?

Southwark Notes meet with Artangel after we wrote a very strong condemnation of their idea to use evicted homes as raw material for a public artwork. It was an interesting meeting where we expressed our dismay at their ignorance and insensitivity around the site itself, the Heygate Estate. After this meeting, we received a poorly argued letter that the Pyramid would not be used by the Council as good P.R for their regeneration scheme and that the art work could be interpreted in many ways, some good and some bad. For us, this liberal argument about how art is open to raise questions was not enough to satisfy our dismay at both Artangel’s and The Council’s desire to simply see the Heygate as something that can be played with for a mostly non-local art audience. We argued that the politics of the site and the cruel displacement of hundreds of people from their community was more important than being culturual privileged enough to get whatever you want when local people had not been able to access any democratic, dignified and accountable process regarding the regeneration process.

We offered numerous times to put Artangel personally in touch with four local groups who have been active for years in campaigning for a fairer regeneration process with benefits for all and not just wealthy home investors and buyers but they did not want to meet these groups.

We have not had any conversation with Mike Nelson nor do we know what he thinks of the cancellation of the Pyramid work.

Do you know Mike Nelson´s personal opinion on the social and political conflicts generated by the proposal? Do you think that if Mike had been in touch with the community; if he Have proposed the project to the community and had been working with them from the point of view of the encounter between the social and the artistic, the management of public money, etc. Do you think the reaction to the the pyramid would have been different?

The way the Artangel Pyramid work came to our community was very similar to the way the developers in the regeneration scheme came too. They turn up one day and tell you what is going to happen. If Artangel had attempted to actually ask local people what they thought of this Pyramid they may have found some sympathies and an actual process to learn and find out whether it was a good idea. Instead they chose to believe that their status and prestige meant that a) the Pyramid was obviously a ‘good thing’ and b) that they could get their way because that’s what they expect.

Southwark Notes and the people we worked with to oppose the Pyramid outright are happy that the Pyramid will not happen now. We began to oppose it with the belief that it should not happen and that refusing this colonialist-type attitude of seeing working class areas as ripe for doing whatever you want too it is the only way for communities to stand their ground and demand open and accountable community decision making

Algunos Links

http://heygate.github.io/index.html

http://internationaltimes.it/open-letter-to-artangel-2/

https://southwarknotes.wordpress.com

https://southwarknotes.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/artangel-swark-notes-emails.pdf

– See more at: http://www.nosotros-art.com/opinion/el-heygate-y-su-piramide#sthash.cdlJEnQH.dpuf

Just parking this here for the future: