The following page seemed much easier (for us) to take excerpts and images from the comprehensive booklet ‘Artists in East London‘ developed by Acme Studios that provides an introduction to the history of artists in East London from 1960 to the present day. It contains a large and detailed account of artist’s occupation of the empty Butler’s Wharf warehouses in Bermondsey as well as the long history of artists and Dilston Grove chapel in Southwark Park. Then we added in our art and regeneration bile re: Terence Conran’s ultimate yuppication and touristification of Butlers Wharf and thus the knock on effect Shad Thames.

BUTLERS WHARF: ARTISTS AS PIONEERS

“The Butlers Wharf story charts the classic case of artists as pioneers who find low-cost studio space in neglected inner city areas, move in, preserve and renovate causing rejuvenation within a few years, thus drawing attention to the area and ‘lifestyle‘ possibilities, ultimately being forced out by the property market. It describes the establishment of a community of independent artists in studios by the Thames, rendered homeless again through development…

The wharf was built towards the end of the 19th Century to store the influx of dry goods and spices being imported from the Empire and was finally closed in 1971 when the London Docks became uneconomic, through containerisation of cargoes and de-casualisation of the docking workforce, which led to their relocation outside London further down the Thames at Tilbury. Consequently by the early 70s, like much of the rest of London’s and other port and manufacturing cities’ 19th and early 20th Century industrial buildings, especially riverside warehouses, they were made redundant, and left vacant.

The owners of Butlers Wharf, the Town and City Properties Group Ltd, decided to rent out the wharves as individual storage and light industrial space in order to offset costs and prevent the buildings becoming vandalised. Alongside several small commercial concerns including spice grinderies, waste rag merchants, a pet food factory, several joinery firms, a porcelain factory, a loom-maker and of course the John Courage brewery, among those first tenants were a handful of artists who independently realised the potential as studio space, and indeed spacious but technically ‘illegal‘ living quarters…

ARTISTS MOVE IN

The occupation by artists dates back to 1971 when ‘A’ block, fronting the river was first colonised, and in all seven of the warehouses were ultimately used by artists between 1971 and 1980. Over the next four years artists proceeded to fill up ‘A’ block, moving on in later years to blocks ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’, ‘X’ , W11 and part of ‘P’, also a separate building in Maguire Street. By the end of the 70s, aside from the organised studio groups of Space and Acme Butlers Wharf became in the process, albeit ad hoc and piecemeal, the largest and most divergent community of artists in London, including painters, sculptors, printmakers photographers, dancers, performers and crafts people…

Each artist separately negotiated a short lease and rent, dealing in the process with the cavalier agent for Town and City, Mr Woods who, expoiting the laissez-faire attitude of the owners positively relished renting out useless warehouse space to a breathtaking variety of individuals.

It is important to remember that because the Town Planning use was designated as ‘warehousing‘, technically all other uses contravened this, and through occupation for studio use both the company and the artists were colluding in turning a ‘blind eye’ to the law.

Hence for a very cheap rent, artists through the particular lease mechanism, which involved going to court, waived all rights of security of tenure, thus rendering themselves in the future liable for summary eviction should the company wish for any reason.

Most of the conversions were done at the artists’ expense, installing electricity and plumbing themselves, and doing the decoration, glazing and partitioning. The early pioneers were successful in obtaining Arts Council studio conversion grants, which averaged about £400 per artist, not a princely sum but covering at the very least the material costs and any difficult technical items. In the early 70s the Arts Council in fact initiated programmes for supporting directly individual artists – there were major and minor bursaries and grants for assisting with artists living and working expenses, and studio capital costs were a major separate programme.

PROPERTY BOOM, POTENTIAL SEEN – THE RIVERSIDE THAT WENT TO BLAZES

By 1979 the bubble just had to burst. As in New York and Chicago, the fate of redevelopment had already befallen St Katharine Dock opposite, which saw many buildings including the Space Studios vacated and demolished to make way for the Tower Hotel luxury yacht marina. Besides Space’s main building, artists Robyn Denny and Dante Leonelli both had independent studios in the St Katharine wharves, and were also forced to move on in the process.

By late 70s presence of artists had contributed enormously to the rejuvenation of the area – so much so that the regeneration potential of cultural activities was appreciated by the local authority Southwark, who proceeded as a protective measure to designate the wharf as a conservation area.

Southwark Council loathed the idea of another Katharine Dock – “like a zoo where you come to gawp at the jet set” as Ward councillor Peter Ward graphically put it at the time. However, Southwark’s intransigence did not put off restaurateur and developer Terence Conran, who together with Town and City director Basil Winham and the chief architect of the Louis de Soissons Partnership Max Gordon recognised Butlers Wharf huge potential and put forward a development proposal for a luxury marina, hotel, office and apartment blocks and a floating pub, espousing the idea that a more ‘chic’ class of tenant would pay much higher rents for the privilege of a view of the Thames

Butlers Wharf was thus destined to be “discovered” all over again, to become ‘yuppie‘ apartments and Italian restaurants.

UP IN SMOKE! BUTLERS WHARF ARTISTS GETS THE CHOP (HOUSE)

At approximately 4 am at the end of August 1979 an electrical fault started a fire in the ground floor workshop of furniture makers. Most of A block was destroyed, and demolition of the affected areas commenced next day, still with some artists resident in the upper floors. This catastrophe suddenly alerted not only the occupants, but the owners and the fire authorities to the real risk of loss of life.

The GLC slapped dangerous structures notices on some of the warehouses, and demanded that the owners make the buildings safe, and bring them into line with current safety and fire regulations. For financial reasons, apart from anything else, this they were understandably reluctant to do, and because of the fundamentally ‘illegal‘ nature of the artists’ occupancy, Town and City took the

opportunity to initiate what was to become the exodus of all the artists.

Those artists in A block immediately affected by the fire who did not make their own immediate alternative arrangements elsewhere, ( to Suffolk in one case, or further eastwards in riverside warehouses) were offered on licence some space in another wharf at the rear of the estate.

Gradually many of the artists drifted away, but in late January 1980 all the remaining artists, now numbering about 60 from the original community of over 150, were sent notices to quit from Town and City, and formed the Butlers Wharf Association to harness resources and seek a solution to the pressing problem of eviction, and the need for new studio space….”

US AGAIN:

At this point us Southwark Notes louts and layabouts interject – The whole area was then subjected to what we laughingly found out has been called “Conranisation’ after Terence Conran, haute bourgeoisie, culterati and prime businessman (first and foremost) developed the area into ‘a combination of luxury apartments and offices and to make it a gastronomic destination‘. Four or five pretentiously European-style restaurants lurk on the waterfront being the haunt of tourists stuck out by Tower Bridge with nowhere else to see and the City workers who bought the luxury flats above. Even the 1990 the property crash and Butler’s Wharf Ltd going into administrative receivership in December 1990, owing the Midland Bank seventy million pounds, failed to stop the ruination of Butlers Wharf!

Anyhow, it’s still all very late 90’s and stuck in that time period of flashy suits and red frame glasses, nice shirt and braces, of course. The perfect plonking down overnight of the Conran dream. Timeless and spectacular with a winter Dickens chill and fog off The Thames but nary a boat to be seen. Just the clanking of coinage and the rustle of 20’s. Unlike The South Bank, Butlers Wharf river front gives no real reason to walk and enjoy the Thames. It’s very dull there in its inorganic stasis.

No doubt the slim degrees of separation in the late 1970’s between Conran and some of London’s then Boheme gave Conran the eye for the place as he headed South for some nights out! Derek Jarman, who we talk about below says this more or less in his early book ‘Dancing Ledge‘ from 1984:

We can plot out the weird connections of Conran to Butlers Wharf briefly in the hope that this catches the twinkle of the old warehousing in the man’s eye. Artists being in awe of the space, light, cheapness and ambiance of the river and sometimes a feeling of slumming it (a whole other story), Conran sees empty buildings as prospects for the construction of residences and restaurants of good taste. Being a pupil at Central School of Art in the late 40’s and then friend of the artist Eduardo Paolozzi he may have been around Paolozzi when he was starring in the amazing film by Lorenza Mazzetti ‘Together’ (1956) or at least heard tales of it.

Together is the tale of two non-local folks who are both deaf and mute wandering and working around the Butlers Wharf area so the whole tale is big on this very visual experience of the post-war landscape and docks. Often hallucinatory in moments like the local pub and street market, the tale doesn’t end well. In the pics above you can see Paolozzi walking and working at Butlers Wharf. He is the bigger one in the pics!

Another strange-ish twist is the connection between Conran and the Sex Pistols who played at Butlers Wharf at the Valentines Day Ball 1976 organised by artist resident Andrew Logan, a ‘key figure in London’s cultural and fashion life’ and who stills lives in Bermondsey in The Glasshouse, Melior St. Sebastian Conran has already given the Sex Pistols there first gig in Central St Martins (where his dad had studied) in November 1975. Southwark Notes has harboured a 20 year fantasy that Terence Conran was on the famous 1977 Jubilee Sex Pistols boat trip publicity stunt up and down the river, past of course the empty artist-full Butlers Wharf. Maybe this is where the twinkle began to the tune of ‘Pretty Vacant‘? We may be right. We may be wrong! (Update: Feb 2013 – we were going through some old notes from the back of the filing cabinet and found this from Terence Conran by Nicholas Ind, (1996) – ‘Terence had first noticed it when he had been on a riverboat party and he had asked Fred Roche to investigate“. Hilarious! Fred Roche was a 80’s Conran business partner in development, both being directors of Butlers Wharf Ltd (alongside other tycoons and all)

At least Jarman and the others were a bit more aware and critical of the global processes at work at Butlers Wharf and Bankside that kept them as artists jumping from one future development site to the next. Without being nostalgic for an (intuited) older artistic sensibility, the Conran yuppie flats / posh restaurant project and the accompanying Young British Artists crowd that made use of the ex-industrial spaces in Bermondsey in the same period was always more about money and celebrity status than any useful practice of art and it’s possible adventure of looking and understanding the world both sensually and critically.

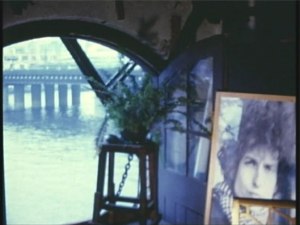

Stills from early Jarman Super-8 films, Bankside 1972-1973. My Tea Shop was still there until 2018 rebranded at 1 Duke St Hill, SE1 as My Tea and Coffee Shop. Now it’s turned into a kebab shop! You can see it in Derek Jarman’s Super8 film ‘Studio Bankside’, 1970-7

—

DEREK JARMAN in BANKSIDE & BERMONDSEY:

“In 1968, Jarman had his first taste of riverside living in a house on the South Bank awaiting demolition, where he shared studio space with Peter Logan and the painter Tony Fry. Shortly afterwards he moved to a warehouse at 51 Upper Ground, near the corner of Blackfriars Road, a place that was to become ‘a Mecca for London’s avant-garde’ with its parties thrown by Jarman with Peter and Andrew Logan. Shortly afterwards the building was demolished to make way for the IPC Tower. Next stop was 13 Bankside ‘on the top floor of a riverside warehouse alongside Southwark Bridge. To cope with the cold in the warehouse, Jarman famously set up a greenhouse for his bedroom. Bankside too became famous for parties, and for film showings as Jarman began experimenting with Super 8. In summer 1972, Jarman had to move again to make way for another demolition, filming a final walk of the area called ‘One Last Walk One Last Look’.

The following year, Jarman moved to a new home/studio in a semi-derelict warehouse at Butler’s Wharf, next to Tower Bridge. Jarman lived on the third floor of Block A1, with neighbours including Andrew and Peter Logan. On the waste ground next door Jarman filmed the ritualistic fire scenes for ‘In the Shadow of the Sun’, with a fire maze, candles and flashing mirrors. The finished film was finally released in 1981 with a soundtrack from Throbbing Gristle”.

From a discussion of the placing of flowers and candles in and around Butlers Wharf on the 10th anniversary of Jarman’s death in February 1994 on SE1 Forum here. Long ago it was now, but some of Southwark Notes were the candle and flower layers that night! *-)

A useful website is 2B Butlers Wharf by David Critchley with lots of pictures. 2B was “2B Butler’s Wharf was rented in 1975 by a group of friends who had first met while at art college in the Isle of Man and Brighton. Within weeks they were joined by recent art graduates from Newcastle, Leeds and Maidstone, along with a single artist met by chance whilst looking for a studio along the wharf. This disparate collection of individual artists soon became a cohesive group around the practicalities of working in time-based media in such a demanding yet inspiring location. The 2B Butler’s Wharf ‘group’ as defined by those who took part in the 1976 Group Show were John Kippin, Belinda Williams, Martin Hearne, Kevin Atherton, Mick Duckworth, Steve James, Dave Hanson, Alan Stott, Kieran Lyons, Alison Winckle and David Critchley.”

Further info is also provided by Critchley here with lots of leaflets for public shows: “The first person to put on a publicized live performance at 2B was Kevin Atherton in November 1975. This event confirmed the potential of the space and its location as an ideal venue for cutting edge time-based art work. A combination of word of mouth, individual mailers and contemporary arts publicity soon put the space on the arts map as a performance art venue. In May 1976, regular Saturday evening shows began with presentations by members of the original group, quickly extended to shows by close associates and then opened to all artists wishing to use the space for presentations of their time-based work. In eighty shows over two and a half years, thirty involved film projection, a dozen used video, a further dozen were sound pieces; several used light as a primary element, some were pure performance art, while many used combinations of different media”.